Introduction

Access to literature is one of the most important tools for any entomologist.

It not only facilitates species identification, it allows to place observations in context. Where does a species occur, what does it do in its life, did my findings confirm, expand or challenge existing knowledge?

Navigating literature can be challenging, especially in entomology. You’ll often find yourself consulting papers that are decades old, sometimes even centuries. It’s quite typical that you won’t find a comprehensive monograph about one particular genus. Instead, you’ll have to combine scattered information from multiple papers.

Entomological literature differs in a few aspects from typical scientific publishing:

- Historical papers stay highly relevant forever: Taxonomic literature never becomes outdated, as original descriptions always need to be consulted.

- Taxonomy, the framework needed to identify species and distinguish them from one another, is neglected by academia. This is another reason why historical sources are often the most recent ones we can use. Updating literature for over 60,000 weevil species, while applying modern research techniques, would require much more resources.

- Higher prevalence of small journals: Contributions on host plants, life history, distribution, but also taxonomy are usually not accepted by major journals, but highly relevant for entomology. Small journals are also popular with amateurs, who like to publish for free and don’t have to care about impact factor.

- Both historical papers and small journals can be print-only and, even when published electronically, tend to lack a DOI and Crossref registration. This makes them difficult to find on platforms commonly used by researchers (e.g., Web of Science, Google Scholar). Managing bibliographic data (for citations or to organize a literature collection) becomes more tedious, since information cannot be automatically retrieved via Crossref, it has to be entered manually.

- But: Each taxonomic paper has a well-defined scope, usually focusing on a single taxonomic group in a specific region. This makes it easier to locate literature using keywords. Searching for keywords would be more complicated in fields dealing with more abstract and less consistently named topics.

- Many authors were highly prolific and wrote consistently about the same topic (their taxonomic group of focus). This makes it more convenient to sort literature by author instead of other categories.

Obtaining Scientific Literature for Free

How to Access Scientific Papers Online for Free

Firstly: Others who are interested in the same field may have already accumulated a lot of literature as PDF files. Ask if you can get a copy of the whole collection!

Asking researchers for copies of their papers

Scientists never get payment when they publish in academic journals. Usually it’s the other way around: The journal publisher gets paid by the authors (or their funding body) to publish the paper. There are few exceptions, when the journal’s expenses are paid from elsewhere.

Because researchers do not profit from sales, their main goal is to have their work read and cited.

When papers were published print-only, it was customary that authors would receive a number of printouts (about 30), which they distributed amongst their peers. In German those printouts are called “Sonderdrucke” or “Separata”, in English they seem to be “offprints”. A literature collection back then consisted of cardboard boxes, which held offprints as well as photocopies made at libraries. The collections were usually sorted alphabetically by first author and the year.

Offprints stored in cardboard boxes, sorted alphabetically by first author.

Offprints stored in cardboard boxes, sorted alphabetically by first author.

Offprints are largely replaced by PDF files. If you cannot read a paper for free, you can ask the authors if they can send you a PDF. They will almost certainly be happy to do so. There are even online platforms to facilitate this, such as ResearchGate.

To find an entomologist’s email address, look for other papers. They usually contain contact information (at least for the corresponding author).

Keep in mind that the situation is different for books.

Biodiversity Heritage Library

I think the most valuable resource for taxonomists is Biodiversity Heritage Library (BHL). The project also collects contemporary literature when copyright allows, but its main focus is digitized historical publications. Papers older than 100 years are usually already available on BHL. Without BHL, researchers in most countries would have no access to these historical papers! Even in countries where access to historical literature is easy, we would spend much of our time waiting for interlibrary loans. The impact of BHL in facilitating and accelerating taxonomy cannot be overstated!

ZOBODAT

A smaller database, especially for journal articles written in German, is ZOBODAT. It can grant access to historical papers, but most importantly to journals that are published by small amateur societies. Some of them are published in print only, not listed in Crossref, or without peer review. But they often contain valuable data not found elsewhere, such as where species occur and how they live and reproduce. Such information is valuable (also for academic research), but not valued much by academia in general. This is why amateur entomologists are often the only ones who publish about those topics.

If your amateur society publishes a print journal you’d like to have on ZOBODAT, you might be interested to know that ZOBODAT also offers to scan literature to make it accessible online.

SciHub

Another resource that can grant access to literature is Sci Hub. It does so without respect for copyright law and is therefore illegal. At least I think it’s illegal. I’m not a lawyer. I mention it anyways, as it is tremendously common in the scientific community to use SciHub. It can only access papers with a DOI.

Scanning Literature

Some literature cannot be accessed online. This includes many books, small amateur journals, and those journal articles that are too young for BHL but too old for the internet.

Buying is expensive (or the book out of print), so if possible, it can be a good alternative to borrow it from a library. Some libraries can order literature from other libraries via interlibrary loan, especially those at universities. Sometimes you’ll get a scanned copy on paper; sometimes you’ll get the original and have to scan it entirely by yourself. Usually you will not receive a PDF file directly.

Managing and Accessing PDF Collections

If you store literature as PDF files, you’ll accumulate a collection that can easily contain several ten thousand files. There are two main use cases to access/navigate that collection:

- 1) You need to read a specific paper (“Where did I put the PDF of Ter-Minassian 1988?”)

- 2) You search for information but don’t know a source yet. (“Do I have something to identify Lixinae: Cleonini?”)

Storing PDF Files in Zotero

Best practice would probably be to manage the collection using a reference management program such as Zotero. The software is free, open source, and covers all features we need:

It can store bibliographic information (author, year, title, etc.), but also the PDF files themselves. The collection can be searched, including not only bibliographical information but also the text within PDF files.

Most important features:

- Add files to the library via identifier (ISBN, DOI): Zotero will automatically fetch bibliographic data from data infrastructure like Crossref. If the paper is open access, Zotero will also fetch the PDF file and attach it to the bibliographic entry. If the paper is not open access but you have the PDF, you can attach it manually.

- Add files to the library by “drag and drop”: Zotero will add the PDF file and try to fetch bibliographic data from the file. In the case of modern papers that were directly published as PDF, it can find the DOI in the file and fetch a complete entry. A fascinating feature is that Zotero can even fetch bibliographic data from scanned files (if they have OCR). Usually this includes only the title and sometimes the author name; the rest has to be added manually.

- Searching the PDF library: In the search field, you can control if you want to search only “Title, Creator, Year” or “Everything”, which includes the full text. If you have files with many pages, you should adjust the settings for indexing, as only the first 100 pages are indexed (and thus searched) by default.

I use Zotero almost exclusively to manage bibliographic data (references) to create citations for scientific writing (there are plugins for LibreOffice and Microsoft Office). I don’t really use it to manage PDF files, except for papers on “cutting edge” fields such as bioinformatics. Those are usually published open access in big journals, and I need them only for specific projects. To get bibliographic data as well as the PDF file into Zotero, it takes only a few clicks to copy/paste the DOI.

Papers on entomology or taxonomy are often historical or published in small journals without DOI. I’d have to add the files manually and enter some bibliographic information by hand. This would work if I were starting from scratch, but I have already received too much literature from others to start with this enormous task.

There is another problem with Zotero: it’s not super straightforward to get your collection from one computer to another or to share your collection with colleagues. The preferred method by Zotero is “Zotero Sync” (300 MB for free; to get more, you have to pay), which also includes the option to make shared libraries for groups. Another method, also suitable for getting a backup on an external drive, is to copy the data folder. I expect this to work well when moving to a new computer. However, I’m not sure if there is a way to “merge” two data folders (if you already have your own but want to incorporate that of a colleague as well).

The data folder is not intended to be human-readable. It contains one directory per PDF file, and those directories are named with Zotero-specific identifiers, not something like author names. On the other hand, the PDF files themselves are nicely named in a very human-readable syntax. They could easily be extracted and sorted in another folder structure (e.g., alphabetical by first author).

Storing PDF files without additional software

I’m already spending too much time with all of those tasks that are part of entomology but not strictly weevils. To save time for the precious things in life (identifying weevils, the occasional chat with another human), I decided against managing my PDF files tidily in Zotero. Instead, I store the files directly in directories on my hard drive. I just dump them there, the directories are sorted only by first author.

The most important aspect is to name the files consistently!

File names need to contain at least the first author and the year.

Finding files by first author and year is easy. Including second authors can be problematic: Dieckmann_1983.pdf, Dieckmann_Mueller_1984.pdf and Dieckmann_etal_1983.pdf are sorted in very different positions alphabetically, even though you’d expect them to be close together. Searching files is also more straightforward when you have a clear structure. However, some search tools such as “KFind” allow to search files by file name using * as wildcards. Searching “*Dieckmann*1984*” will find both “Dieckmann1984.pdf” and “Dieckmann_et_al_1984.pdf”.

For example, you could name the files “FIRSTAUTHOR.YEAR.HUMAN-READABLE.pdf”, like Dieckmann.1971.RevisionApionCerdoGroup_Oxystoma.pdf for example. The part behind the year is just for you to get an idea of the content, its not the real title. When you’re confronted with a list of search results, you don’t want to click each file to identify the one youre looking for. Those weevils where classified in Apion in 1971, but the “Apion cerdo species group” is now in the genus Oxystoma. I added that to the file name for my own convenience.

In my early days, I stored PDF files sorted by topic. There was one directory for “beetle identification” and one for “beetles everything else”. Each directory had multiple subdirectories for various beetle families and biogeographic regions. This is an invitation for chaos, as many papers are covering more than one topic. It’s very time-consuming to find something in such a folder structure.

Often I search for literature without knowing a reference. For example, I need to check if I have an identification key to the genus Phaedropus. To find out, I search the full texts of the whole collection with Recoll (see below). To search entomological literature, it is extremely useful that we can use scientific names as search keywords.

As there are useful tools to search for files, I don’t spend much time curating the collection. I keep different PDF collections separate instead of merging them. This creates some duplicate hits in my searches, but it’s not really a huge problem. I’m thinking about creating a small Python program to normalize file names and to merge collections while identifying duplicates, but it’s not something I’m actively working on.

I still maintain some folders where I store files that I need really often (or for specific projects), and it makes sense that they are stored by topic. But each of those files has a duplicate in the main collection.

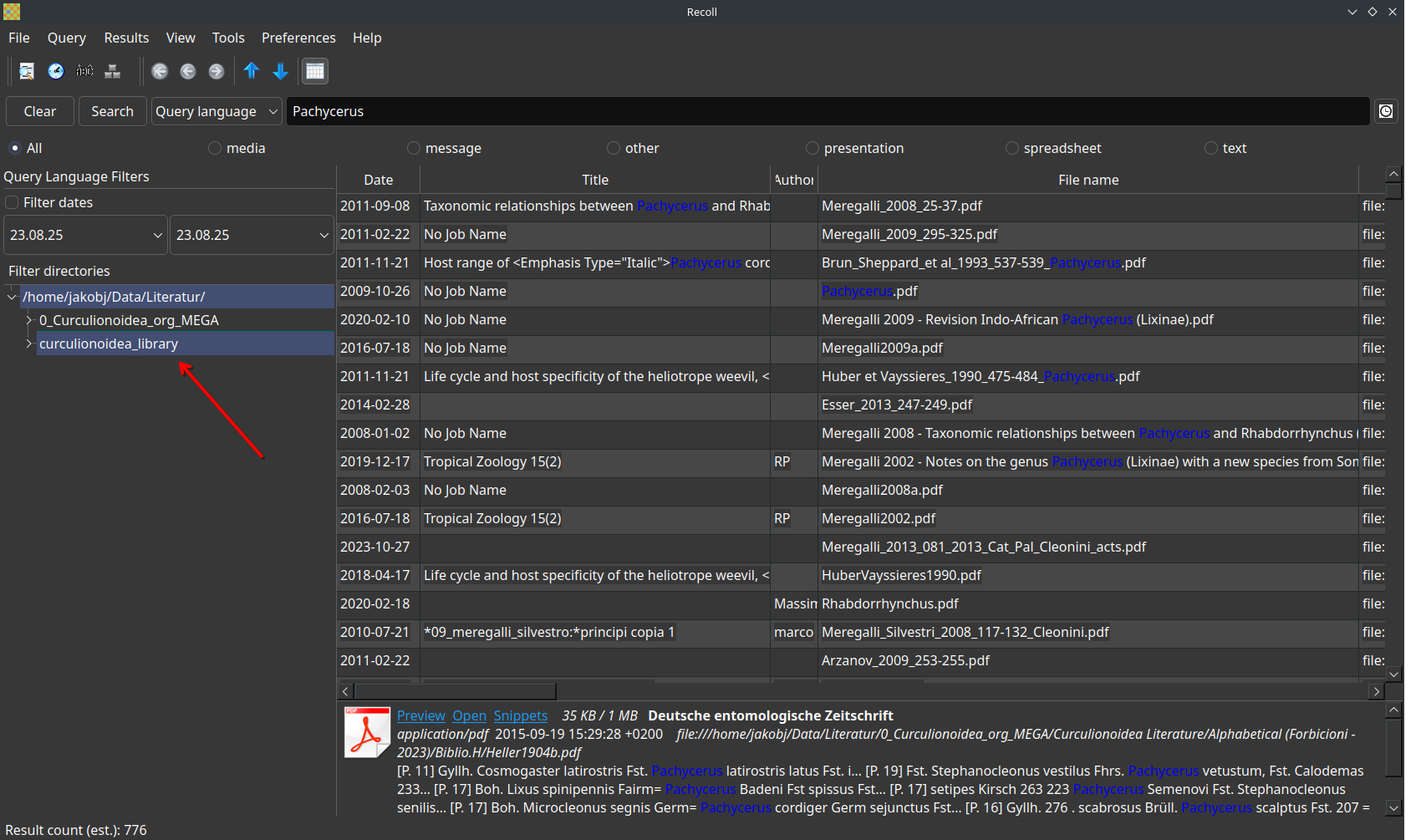

Searching the text content of PDF collections with Recoll

Recoll is a local search engine for PDF files, but also other text-containing file formats. It works similarly to a Google search, but for files on your computer.

This is something I learned from Lutz Behne. He used a similar program, which was already quite old and probably not available for Linux.

To get started, you’ll have to set up an index. The index is created by the program to be able to search efficiently.

Creating the index takes an hour or two for several ten thousand files, but afterwards each search is done instantly. You can specify directories to index, and while searching you can include and exclude them as you like. This is useful if you index more than one separate collection. You could even index your Zotero data folder.

I search mainly for taxon names. The results are ranked by relevance, and typically if I search for a genus name, the most recent revision of that genus is among the first results. I have also searched for localities (e.g., island names) and found relevant literature that would have been difficult to discover elsewhere.

Recoll, graphical user interface. In this case I have searched only one of my two directories for weevil literature (curculionoidea_library is selected; the download from curculionoidea.org isn’t). You can select or deselect any combination of subdirectories as well. In the results table, you can see why it is important that file names have a human-readable part to give an idea about the file content: Most PDF files don’t contain the title of the publication in PDF metadata, not even files downloaded from ResearchGate!

Recoll, graphical user interface. In this case I have searched only one of my two directories for weevil literature (curculionoidea_library is selected; the download from curculionoidea.org isn’t). You can select or deselect any combination of subdirectories as well. In the results table, you can see why it is important that file names have a human-readable part to give an idea about the file content: Most PDF files don’t contain the title of the publication in PDF metadata, not even files downloaded from ResearchGate!

You can view the results in different modes; I prefer a simple table. Double-clicking an entry will open the PDF. You can specify in the settings which PDF reader you’d like to use. You can also right-click and select “open parent folder”. The folder where the PDF is located will open in your standard file explorer, and the file will already be selected. You can now easily copy it to another directory or drag and drop it as an attachment in your email program.

I think Recoll is pretty straightforward. You can get started without an extensive tutorial. The documentation is very helpful. During indexing you’ll probably get soft errors. Check the log file to learn more about them. In my case the problem was that Recoll cannot read .doc files on its own, in the log it asked me to install the separate package “antiword” to fix that.

Recoll will only search within the index. Whenever you add new files to a directory, you have to update the index (or rebuild it from scratch) to include the new file in the results!

The index can be configured to update in real time or on a regular schedule, but I don’t think that’s necessary since another background task could slow down the system. I just update it manually whenever I feel it’s needed.

Additional Information

Can Files be stored forever?

As entomologists, we are constantly thinking about long-term stability. We take every step necessary to ensure our collections remain informative for at least the next 200 years. For example, we use acid-free paper for labels. You heard correctly: keep your LSD blotters out of the beetle collection! Shouldn’t we apply the same mindset to digital resources?

There are two main problems with file storage:

- File formats may become unreadable. This is something older generations may be familiar with, but it has happened to me as well: I’ve received files several decades old with file extensions I didn’t recognize, and no program could open them. Software written for older systems (e.g., Windows 98) often won’t run on today’s computers or is not accessible at all. The tools we use now may be just as inaccessible in 30 years (software rot). Most software depends on external software (environments), which makes long-term use difficult.

The problem of outdated file formats can be mitigated by choosing formats suitable for long-term storage. The format should be widespread and commonly used, a niche format is more likely to loose widespread support. Proprietary file formats are generally unsuitable, so open formats are preferred.

For PDF, its a bit more complicated. The PDF format itself is open and so widely used that it will certainly be accessible in the future. But PDF can embed other files, such as images, in their original format. The PDF/A (A for archive) standard tries to include as much as possible within the file, so that it doesn’t rely on external resources (such as fonts), which may not be available in the future. Storing PDF in PDF/A can increase the size of the file.

- Files can become corrupted during transfer or storage. This can happen if the storage medium reaches the end of its life, but corruption can also occur earlier, at a lower rate.

You should backup your data anyways, and you can replace a corrupted file from the backup. However, corruption can initially go unnoticed. I don’t check my files regularly, most aren’t opened for years. To detect changes in files, you can generate a checksum. A checksum is calculated from a whole block of data, effectively reducing the information to a short number. The smallest change (flipping of a single bit) in the whole block will drastically change the result. It’s good practice to compare checksums at least before and after a file transfer, for example when you make your backup.

In compressed or encrypted files, even a tiny change can have a devastating impact. Think of file compression like this: AAAABBCCC gets compressed as 4ABB3C. If I change only one character in the uncompressed file, the consequences are smaller than in the compressed file. In an uncompressed image file (e.g., uncompressed TIFF), a single bit flip would affect only one pixel, while it can distort large parts of the image in a highly compressed file. I’ve seen this in JPEG files.

Batch-Processing of Scans

Processing your scans can be semi-automated using command-line tools, like ImageMagick. This single line will rotate every JPG image in the directory by 90 degrees:

magick mogrify -rotate 90 *.JPG

#"magick mogrify" is the command by ImageMagick to edit files in place (see https://imagemagick.org/script/mogrify.php)

#-rotate <VALUE> is the option to rotate the image

#The * in the file name is a wildcard to match every file name starting with whatever and ending with ".JPG"You can also split two-paged scan images into single pages and much more. No need to do such tasks manually!

ImageMagick can work with PDF files, but it will rasterize them (convert vector graphics into pixel graphics), which can be undesired in some cases. Scans are usually already pixel-based.

OCR: Making PDF scans searchable

OCR (Optical Character Recognition) is the process to “make a PDF searchable” by adding a machine-readable text layer above the image. If you can search, mark and copy text, the PDF already has OCR.

There are various programs to OCR a PDF and the results vary in quality. A major problem for us is that scientific names are “unusual” words, but they have to be recognized correctly as they’re the terms we’re usually searching for. Lutz Behne, a weevil researcher who scanned a lot of literature, went through many of his scans manually to correct mistakes in scientific names. He even did this for the “Palearctic Catalogue”, which is multiple volumes containing not much text except for beetle names! He told me this took him several weeks. He had a program which displayed both the image and the text layer separately, and he could edit the text layer.

A simple OCR tool, which you can use in your browser, is PDF24.

I wouldn’t upload sensitive information to a web tool.

I have spend some time using OCRmyPDF, a Python command-line program. But honestly, the results by PDF24 are fine, and while OCRmyPDF offers more option to tweak and optimize things, it doesn’t work as smooth without tweaking. The documentation of OCRmyPDF is very good and also provides insights into the structure of PDF files and how OCR works. I recommend to read it if you’re interested.

While OCR results from recent software seems to be very good in general, I sometimes notice bad OCR in older files, and redo the OCR to correct it. This also seems to be an issue for Biodiversity Heritage Library.

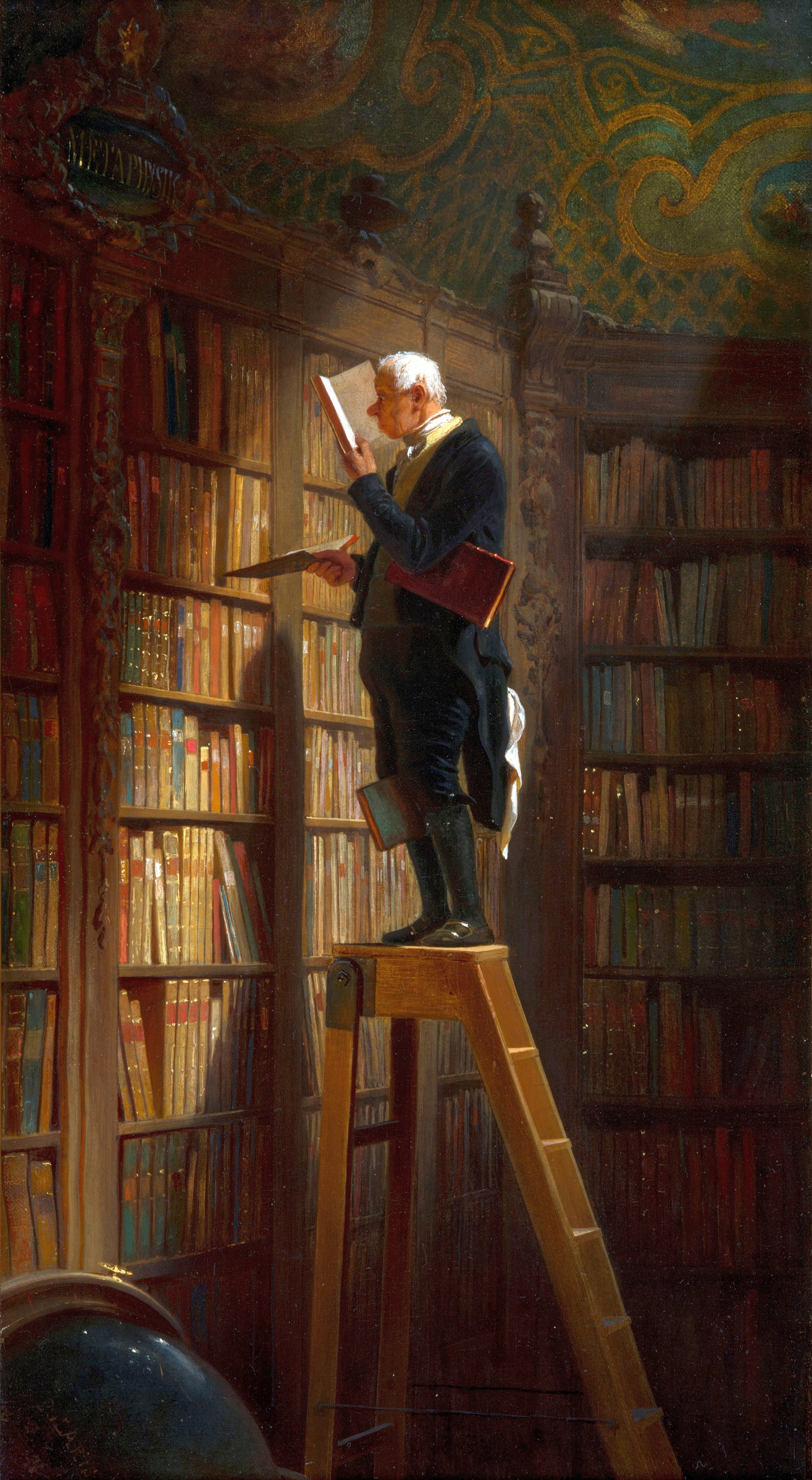

“The Bookworm” by Carl Spitzweg, around 1850. In his paintings, Spitzweg often made fun of bourgeois male characters who indulged in their special interest, oblivious to the “real world” around them. A bookworm is someone who reads a lot, but most importantly the term alludes to various insects that devour books. I think what Spitzweg wanted to depict here is probably the ignorance of the bibliophile towards the hidden insect life around him. What unfolds around the central character is actually a phantastic habitat for xerophilous insects that are capable to live from cellulose. They can even make water from paper to survive under dry bookish conditions! Only a blockhead, an ignoramus, a thorough dullard would waste time in an 19th century library to read about “metaphysics” instead of admiring the hidden life between the pages! While todays libraries are rather dull places due to Integrated Pest Management (except for the occasional paperfish, Ctenolepisma longicaudatum), they where sprawling with life back then: Voracious book scorpions (Chelifer cancroides) preyed on booklice (Psocoptera), mischievous little creatures which spent their days nibbling on the bindings of horrendously valuable books. Larvae and adults of various beetles are tunneling the books. Under moist conditions, this can include cossonine weevils such as Euophryum confine or Pentarthrum huttoni. When standing in silence, you could hear the sound of destruction echo through the library: Deathwatch beetles (Xestobium rufovillosum) are on their search for a mate. Most insects would find a mate by smell, but smells don’t carry far if you’re spending your life within a book. Instead, they hammer their head against the pages. If someone answers with another vibration, they move towards that direction. And if they’re really vibing with each other they’ll marry each other (19th century, don’t forget) and give birth to a new generation of bookworms.

“The Bookworm” by Carl Spitzweg, around 1850. In his paintings, Spitzweg often made fun of bourgeois male characters who indulged in their special interest, oblivious to the “real world” around them. A bookworm is someone who reads a lot, but most importantly the term alludes to various insects that devour books. I think what Spitzweg wanted to depict here is probably the ignorance of the bibliophile towards the hidden insect life around him. What unfolds around the central character is actually a phantastic habitat for xerophilous insects that are capable to live from cellulose. They can even make water from paper to survive under dry bookish conditions! Only a blockhead, an ignoramus, a thorough dullard would waste time in an 19th century library to read about “metaphysics” instead of admiring the hidden life between the pages! While todays libraries are rather dull places due to Integrated Pest Management (except for the occasional paperfish, Ctenolepisma longicaudatum), they where sprawling with life back then: Voracious book scorpions (Chelifer cancroides) preyed on booklice (Psocoptera), mischievous little creatures which spent their days nibbling on the bindings of horrendously valuable books. Larvae and adults of various beetles are tunneling the books. Under moist conditions, this can include cossonine weevils such as Euophryum confine or Pentarthrum huttoni. When standing in silence, you could hear the sound of destruction echo through the library: Deathwatch beetles (Xestobium rufovillosum) are on their search for a mate. Most insects would find a mate by smell, but smells don’t carry far if you’re spending your life within a book. Instead, they hammer their head against the pages. If someone answers with another vibration, they move towards that direction. And if they’re really vibing with each other they’ll marry each other (19th century, don’t forget) and give birth to a new generation of bookworms.

I wrote this more as an invitation to exchange ideas than as a definitive guide. How do you organize your PDF library?